The construction of modern cities in the Americas perpetuates a history of exclusion. To the promises of modernization and emancipation, the postcolonial societal order responds with new strategies of control and segregation. Monumental planned cities such as Washington, DC, and Brasilia are the apex of such practices; they employ different urban architectural idioms to represent these contradictions. Artists have engaged with questions related to these histories throughout the twentieth century, both singing the marvels of urban life and chronicling their margins.

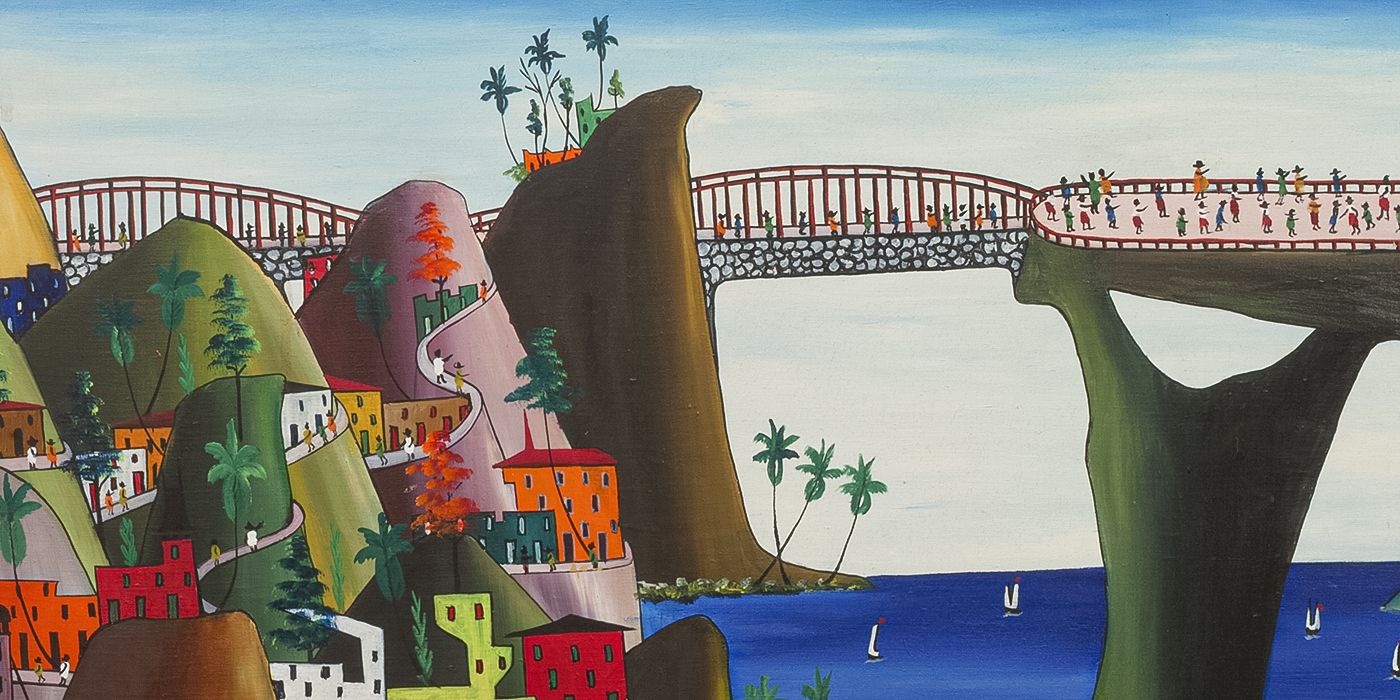

Juxtaposed in the first part of this section, the works by Préfète Duffaut and Asilia Guillén are epic renditions of cityscapes where architecture, nature, and human presence come together. Whereas Guillén creates a fantasy in which artists and national heroes congregate at the Pan American Union headquarters in Washington, DC, Duffaut builds utopic cities based on the topography of his native Jacmel in Haiti.

Asilia Guillén

Emblazoned in orange hues cast by the sunset, the Momotombo Volcano — el cono gigantesco, “calvo y desnudo”1 — rises above the gently curving coastline in Asilia Guillén’s picturesque Lago Managua (1953). The landscape dates to early in the artist’s painterly career, when, at age sixty-five, she took up the brush after first earning success as an embroiderer in her natal city of Granada. Echoes of this previous medium permeate the painting, with its simple outlines and the shadows of the clouds and greenery seeming to evoke embroidery techniques. Even the gentle waves of Lake Managua suggest a textural quality, curving like strands of thread across the water’s surface.

Lago Managua offers a bird’s-eye view of Nicaragua’s capital and its eponymous lake where Guillén developed her distinctive style as a student of Rodrigo Penalba at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes. At least two recognizable structures can be discerned among the city’s winding streets of otherwise generic, pastel-hued buildings: the Catédral de Santiago Apóstol and the Monument to Rubén Darío. More than just an urban landmark, however, this latter memorial to the lauded poet and founder of modernismo serves an important visual cue undergirding the literary context of Guillén’s relatively clichéd, if attractive, landscape scene.

Indeed, for those familiar with Darío’s oeuvre, Guillén’s scene brings forth references to the poem “Momotombo,” first published in the writer’s 1907 book El canto errante [The Wandering Song]. This stirring composition recalls Darío’s initial encounter and ensuing awe upon seeing the volcano for the first time on his arrival to Managua. Like Guillén (though considerably younger, at age twenty-five), Darío moved to the capital to pursue his education, traveling by train from his home city of León. Might this be the same train depicted in the canvas? Was Guillén inspired by other passages in Darío’s verse in creating her composition, with its depiction of “[el] Señor de las alturas, emperador del agua, / a sus pies el divino lago de Managua,/ con islas todas luz y canción?”2

An answer perhaps lies in the poet’s citation of Victor Hugo, who preceded Darío in writing an ode to the volcano in “Les Raisons du Momotombo” [The Reasons of Momotombo], published in 1859.3 Tellingly, Guillén appears to have been familiar with the intricacies of this legacy, as within a year of creating Lago Managua she painted a portrait of Victor Hugo.4 Such works are in keeping with Guillén’s interest in representing people and places of historical and cultural interest, including her painting Heroes and Artists Come to the Pan American Union to be Consecrated (1962), which is also featured in the exhibition Popular Painters and Other Visionaries. Whereas in this later work Guillén makes explicit and easily recognizable reference to international solidarity, Lago Managua reflects a quieter, albeit nonetheless powerful image of national pride to those familiar with its veiled symbols from Nicaraguan culture.

Fractured Spaces

The paintings and prints in this section focus on the theme of manmade construction in nature and feature housing complexes, an outhouse, a porch, a favela, stilt houses, parks, andvillages. Small structures are depicted against a transformed natural landscape while metropolitan skylines are framed by urban gardens. The artists in this grouping capture their experiences within their communities, or they look from afar at the buildings of the wealthy that define the cityscape. These perspectives point to the problematic boundaries between public and private realms. The formal superimposition of planes and lines — in which façades, clotheslines, and light poles appear prominently in the compositions — reflects fractured spaces, both lived and imagined.

About the artists

Born in 1927 in Paulínia, Brazil.

Died in 1997 in São Paulo, Brazil.

Born in a small country town, located in the interior of the state of São Paulo in Brazil, Batista de Freitas was only seventeen when he moved to the state capital, where he found work in a toy factory. When he was fired for drawing during working hours, he became an electrician, the profession to which he dedicated most of his life. Around that time he also began selling his paintings at an outdoor plaza in downtown São Paulo where his work caught the eye of Pietro Maria Bardi, founding director of the Museum of Art São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), who would organize the artist's first solo show at MASP in 1952. Batista de Freitas's first works show views from the streets and squares of the city center, a theme to which he dedicated himself throughout his life. Among the buildings he painted are skyscrapers and monuments considered iconic in the city’s process of modernization, including bridges, bank headquarters, and luxury residential buildings. He also created a large body of work with contrasting views of the periphery of the city, where he lived. In several paintings he also portrayed the MASP building, designed by Lina Bo Bardi and inaugurated in 1968. In 2016 MASP honored the artist with a large retrospective.

Pedro López Cervántez

Born in 1915 in Wilcox, California.

Died in 1987 in Clovis, Arizona.

Cervántez's maternal grandparents were potters in Durango, Mexico, and he lived with his family in Texico, New Mexico, where his talent was first “discovered” by R. Vernon Hunter, the local director of the Federal Art Project. Through Hunter, in the 1930s, Cervántez worked for the Works Progress Administration in New Mexico, where he reproduced paintings of religious images, participated in mural projects, and later joined the Easel Painting Division. In 1936, his artwork was presented in the exhibition New Horizons in American Art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which continued to feature his work in subsequent exhibitions, including the important Masters of Popular Painting exhibition in 1938. Cervántez attended Eastern New Mexico University in Portales for two years, but his studies were interrupted by World War II. In 1940, he enlisted in the US Army and was dispatched to Italy and Germany where he was exposed to European artworks. After the war, he resumed his studies at the Hill and Canyon School of the Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, from 1949 to 1952. Although he is considered one of the first Latino artists to have received national recognition, reception of his artwork diminished in the years following the war. In 2002 he was included in the exhibition Sin Nombre: Hispana and Hispano Artists of the New Deal Era at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Félix Cordero

Born in 1931 in Ponce, Puerto Rico.

He has worked as a cartoonist, toy designer, photographer, filmmaker, and photo retoucher for the advertising industry for more than thirty-five years. In 1949 Cordero received a grant to study with the renowned painter Miguel Pou. In 1953 he moved to New York to continue his studies in art, first at the Manhattan Technical Institute and then, from 1955 to 1956, at the School of Visual Arts. Years later, Cordero also studied at the Winona School of Photography in Winona Lake, Indiana (1969–1971) and the American Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago (1971) before continuing his studies in New York at the Art Students League (1973–1975), the New School of Social Research (1978), and at the Drawing Room (1984–1986). His rich, colorful artworks are realistic representations of the landscapes and architecture of his culture. In the early 1990s Cordero lived and worked in Ecuador before returning to his native Puerto Rico in 1994. He currently lives in Guayama, Puerto Rico.

Born in 1923 in Cyvadier, Haiti.

Died in 2012 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Duffaut is considered part of the first generation of artists to be associated with the Centre d'Art, a cultural center established in 1944 by the American artist and conscientious objector Dewitt Peters, who had been sent to Port-au-Prince to teach English during World War II. From a young age, Duffaut worked as a shoemaker and shipbuilder. He began painting after receiving a vision of the Virgin Mary. A religious impulse may be read into much of his work, which frequently includes images of churches as part of his fantastic cityscapes, whose winding roads recall the mountainous landscape of his natal city. “All of my paintings are a reflection of Jacmel,” he stated in a 1978 documentary about his work produced for the exhibition Haitian Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Similarly, his paintings of divine female figures are alternately interpreted as the Virgin or as the loa Erzulie, a divinity associated with Haitian vodou. Through his association with Peters, Duffaut was commissioned in 1951 to paint the transept murals for the Cathedral of Sainte Trinité in Port-au-Prince as part of a larger decorative project created alongside Philomé Obin, Rigaud Benoit, and other artists connected with the Centre d'Art. An important cultural landmark, these murals were mostly destroyed during the cataclysmic 2010 earthquake. Two years later, Duffaut died in Port-au-Prince. His art is part of the collections at El Museo del Barrio, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Milwaukee Art Museum in Wisconsin, and the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa.

Born in 1887 in Granada, Nicaragua.

Died in 1964 in Grananda, Nicaragua.

Guillén’s initial relationship with art was through embroidery, and her work is associated with the regional cultural tradition of the bordados granadinos, a traditional technique from her hometown. While her early embroideries were mostly floral themes, she later developed more elaborate landscapes depicting her country’s geography and historical scenes about colonization and territorial losses. In 1951, at age sixty-three, she picked up painting and enrolled in La Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Managua under Rodrigo Peñalba. Since she translated her earlier practice into a new medium, her paintings are well regarded for their meticulous detail. In 1957 she participated in a group exhibition of Nicaraguan artists at the Organization of American States (OAS) in Washington DC, followed by a second solo show in 1962. Two years later, the head of the Visual Arts Program of the OAS, Cuban-born art historian José Gómez Sicre, commissioned Guillén to paint a historic scene for inclusion in the Central American Panama Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair. Guillén died shortly after at age 78. Her paintings can be found at the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, DC, El Museo del Barrio in New York, and Fundación Ortiz-Gurdián in Managua.

Born in 1921in Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico.

Died in 1988 in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

After leaving school at a very young age, Hernández Acevedo worked as a shoemaker, sign maker, and cook. In 1947 he entered the Graphic Arts Workshop of the Division de Educación a la Comunidad (DivedCo) through the encouragement of the workshop's director, graphic artist Irene Delano. Unlike other artists at DivedCo who focused primarily on silkscreen, Hernández Acevedo also excelled in the medium of painting. His brightly colored canvases most often depict the streets and buildings of Old San Juan as well as local historical events. He also dedicated a good part of his work to printmaking, including serigraphs of popular neighborhoods in San Juan and Christmas cards. Hernández Acevedo's artworks are part of numerous public and private collections in Puerto Rico, including the Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte de la Universidad de Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, and the Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico.

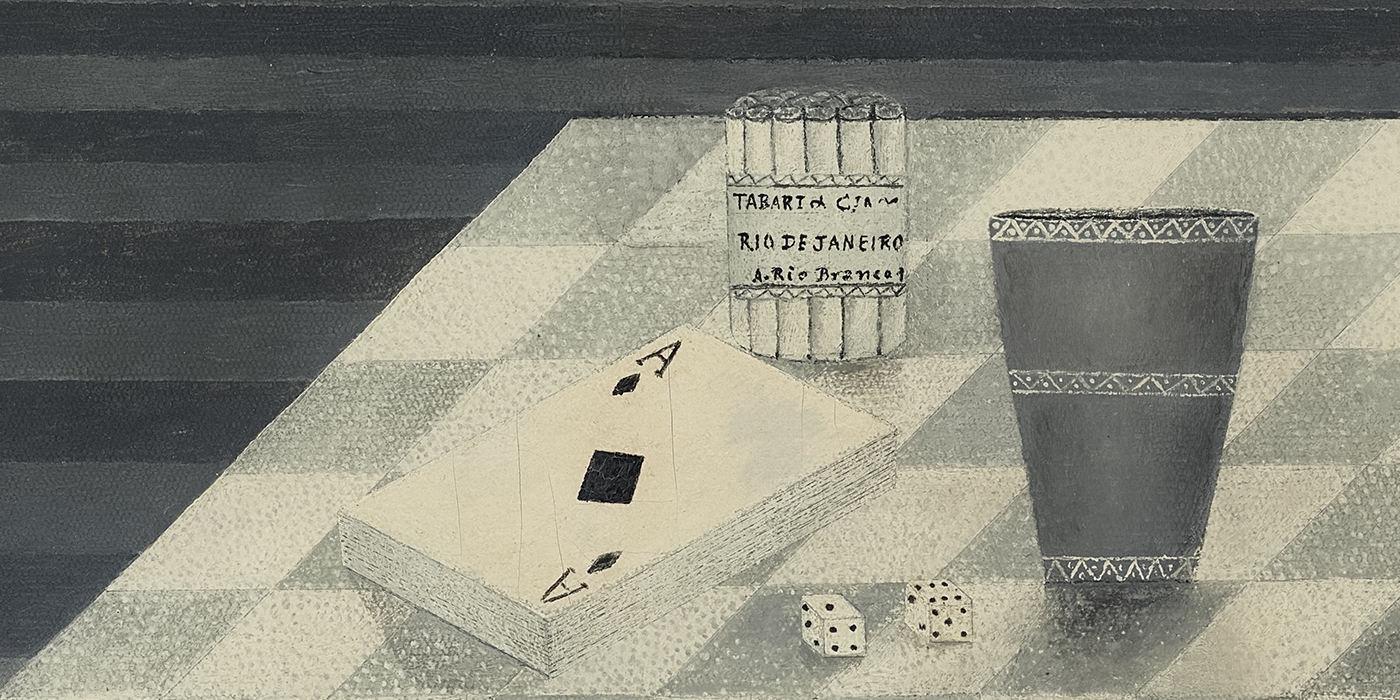

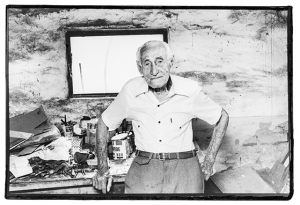

Born in 1900 in Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Died in 1995 in Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Lorenzato was born to Italian parents who emigrated to Brazil to work on the construction of Belo Horizonte, the country's first planned city. He was introduced to the artistic trade at a very early age, when he worked as a decorative painter to the civil construction. In 1918 he accompanied his family back to Italy, where he attended the Accademia Olimpica in Vicenza. Before returning to Brazil in 1948, Lorenzato traveled extensively throughout Europe where he came into contact with the main vogues of modern art. Lorenzato began exhibiting his paintings in the mid-1960s in Belo Horizonte, where local critics promoted them as primitive art. His main genres are still lifes and landscapes, which are known for their saturated colored skies and geometricized favelas that suggest an interplay between representation and abstraction. His works are also well-regarded for their textural surfaces, which he achieved by using a variety of tools, including combs, brushes, and forks. Since his death in 1995, Lorenzato's work has gained more international attention, with solo exhibitions held in galleries in São Paulo, London, and New York.

Born in 1933 in Hato Rey, Puerto Rico.

Died in 2009 in New York City.

After moving to East Harlem in 1947, Villarini studied at the Art Instruction Academy in Minneapolis and the Jo Marino Art School in New York. Villarini's paintings depict landscape scenes of Puerto Rico and Manhattan and include representations of cockfights, working laborers, and local landmarks such as San Juan's La Fortaleza and New York's Central Park. Executed in rich detail that extends to individual roof tiles on buildings and cobblestone streets, Villarini's art is often suffused with a sense of nostalgia. His work is part of the public collections at the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña in San Juan, Puerto Rico; Universidad de Puerto Rico in Río Piedras; Museo de Arte de Ponce in Ponce, Puerto Rico; and the Universidad de Chile in Santiago.